| Back to Back Issues Page |

|

|

The Yes Dog!, Issue #001 -- Dog's understanding of human social cues. September 05, 2012 |

Issue #001, September 4th 2012This is the first ever issue of The Yes Dog! and as I sit here at 5:00 am in the morning I feel excited but I also wonder...What do my readers need and want from it?I always try to bring to you the best advice on dog training and behavior, but if there is anything you think should be added, please send me a quick

e-mail!

We both loved watching freestyle (dancing with dogs) and Frisbee (also a type of choreography but with discs). You couldn't help but smile and clap seeing the human-dog relationship working in such a fun way! Some of the dogs participating were rescued. They went from feisty Fido to charming Barkley with love, patience and training. A truly inspiring sight and fun too. My son particularly loved Flyball, a high speed relay game in which dogs must race in teams. The relay starts with the first dog racing, jumping barriers, releasing and catching a ball then going back so the next dog in the team can start.

Table of Contents

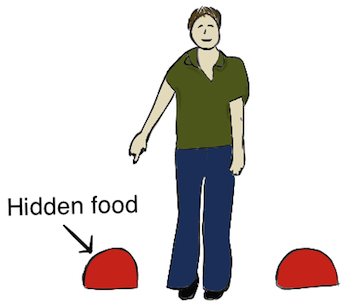

The Science of Dog TrainingHow do dogs understand human cues such as pointing? Theory of mind vs simple associative learning skills.A Review of Elgier AM., Jakovcevic A., Mustaca AE. and Bentosela M. Pointing following in dogs: are simple or complex cognitive mechanisms involved? Animal Cognition Published Online July 2012.For a long time scientists have known that dogs are capable of understanding human cues. In other words, we can communicate with each other. For example, if there are two containers hiding food and the person points to one of them, the dog is more likely to choose that one. It is thought that these skills expressed in cooperative situations are the result of domestication. Chimpanzees, which are closely related to us, seem to be worse than dogs at this task.

Some scientists think dogs require "higher cognitive skills". This means for example that the animal is able to attribute a mental state - intention, desire, etc. - to the person (theory of mind). Other scientists believe that the dog is only using associative learning (Classical and Operant Conditioning). This means that the dog has learned in the past that if he follows the human cues, he gets rewarded. Then, in a new situation he might also follow the human cues. In this last case the dog doesn't actually think the human was "trying to help". He just responded to physical body cues for a reward. Do dogs have a theory of mind or do they just respond to cues because they learn to associate things? This is the questions that Elgier, Jakovcevic and colleagues are trying to answer. How do they go about answering this question? They design experiments to answer smaller questions related to the big one. There are two known phenomena that affect associative learning. These are:

For example: When you start to teach your dog to sit, you give the hand signal, wait until he sits then reward him. You do this several times until he learns that the hand signal predicts that if he sits, he will get a treat. Now you add a verbal command but you say it at the same time you do the hand signal. After several training sessions you try the hand signal alone. What happens? Your pooch does not respond to it! Not because he is stubborn, but because the verbal command has been blocked. The hand signal was a reliable predictor, so your pooch did not need to learn anything about your verbal command. When training a verbal command after a hand signal it is important to do it in the correct order. Say the command followed by the hand signal. Then reward your pet for sitting. This way the verbal command predicts that you will do the hand signal, it has more information. Eventually you can fade away the hand signal altogether.

For example: you teach your dog the command "sit" always in the kitchen. One day you ask your dog to sit in the backyard. He responds correctly! Even though you have never taught him to sit in the backyard. This principle might seem obvious to you, but it's actually hard for some animals to generalize a concept. That is why it is important to train your pet in many different places and with a variety of distractions. Eventually your pet needs to know that sit means sit if you say it or your son does, if you shout it or whisper it and if you say it at home or at the park. In summary stimulus blocking and stimulus generalization are two characteristics of associative learning (not of higher cognitive skills though). The researchers then asked the question: Is the way in which dogs learn human social cues, such as pointing, affected by these two phenomena? The answer is yes. The way dogs learn the meaning of pointing can be affected by stimulus blocking. In the study, if the dog has previously learned that location (right or left) predicts where food is hidden, when a human social cue, pointing with arm and finger to the correct place, is additionally trained, the dog doesn't respond to it as well. Dogs just follow the "location" rule instead because it was previously reinforced. This means that dogs will most likely respond to cues that have a consistent and longer history of being reinforced. When your dog responds to your social cues, does he do it because he understands the social aspect of it? Or because he has learned through many repetitions that following your finger usually leads to food? The results from this study suggest that dogs do learn social humans cues, in part, through associative learning rather than having an innate tendency to respond to them. The way dogs learn the meaning of pointing can also be affected by stimulus generalization. In the study, dogs previously trained to understand a human social cue (direct pointing or standing near the target) can understand a different, and never explicitly trained, social cue (cross-pointing) better than dogs that did not have the previous experience. The authors argue against the hypothesis that dogs understand human social cues through complex cognitive mechanisms, like theory of mind. However they do not directly address this question, so it can't be ruled out completely. Based on their results they conclude that dogs learn to respond to these social cues because they have a history of being reinforced in the past. They finish by stating that associative learning can't be thought of as mechanisms by which animals only learn very simple behaviors. Since, as they demonstrated, dogs can learn complex social cues through associative learning too. Pointing breeds, such as Setters and Pointers, have an innate tendency to point at birds with their head and body. This behavior appears naturally from puppy-hood and it is said to have been bred throughout generations for hunting. I wonder how pointing breeds would perform in this task?

References: Pointing following in dogs: are simple or complex cognitive mechanisms involved? Elgier AM, Jakovcevic A, Mustaca AE, Bentosela M. Anim Cogn. 2012 Jul 17 Train your dog to...Leave it!Wouldn't you love if your dog stop in mid-chase when you said "Fido, Leave-it!"?It can be done! It requires a lot of practice, patience and consistency though. To start, "accidentally" toss a piece of food on the floor. As soon as your dog dives for it be ready to block it. You must not let your pet get it, no matter how hard he tries! As soon as your pooch gives up...Mark and Reward! Repeat many times until he learns the game. Then you can add the cue "Leave-it". And that is how you start teaching your pet the meaning of the words "Leave-it". To learn the next steps in training a reliable "Leave-it" command follow this link. Featured ArticleBest Dog Obedience Training Tip!It is actually very simple:Reward good behavior and ignore bad behavior! That's it!...or is it? This important training tip will take you a long way in building a good dog-human relationship but it won't work 100% of the time. Learn here how to properly use this great advice and when to switch to other training techniques. Your Questions and StoriesThis section is for you to brag about your dog! You can also ask questions (and get answers), tell us your advice or share an interesting anecdote.Your story could be featured in The Yes Dog! And will get its own webpage that you can share with friends and family. Click here to share! This issue's featured story is about Maluco, an Argentinian Weimaraner dog with severe separation anxiety.

A great story about parting with our beloved pets in a positive way. Learn his story and add your comments too! That is all for now. Until the next time,

P.S: Would you like to have your own website? It is easier than you think. I had no knowledge about the web but here I am! You can have yours too... watch the Site Build It! Video Tour.

Copyright © 2012 Natalia Rozas de O'Laughlin. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized duplication or publication of any materials prohibited. Not intended to substitute for veterinary, legal or other professional advice. Consult your vet for advice about medical or behavioral conditions & treatment of your pet. |

| Back to Back Issues Page |